When I entrusted the translation, I sent the game build saying, ‘Thank you in advance. Please play it at least once before starting the translation.’

Quoted from the main article.

Then, two days later, I received the same email.

I cried.

At that time, there was no music.

In January of this year, Indie developer SOMI from South Korea released a new title called ‘미제사건을 끝내야 하니까’ (Because I Have to End the Unsolved Case), which has recently garnered over 5,000 overwhelmingly positive reviews on Steam. The game has received praise for its system, sound, and story, with several reviews containing common expressions like ‘moving,’ ‘relatable,’ and ‘comforting.’

‘미제사건을 끝내야 하니까’ is a game that involves exploring seemingly ordinary dialogue logs to uncover the truth. Players designate key words from the characters’ conversations as tags, combining them to discover new dialogues and unravel the intricacies of the case. This system, while appearing simple at first glance, immerses players as if they were real investigators, leading to unexpected emotional connections as they approach the truth.

Somi, who has been involved in the legal field in Busan, South Korea, for nearly 20 years, has released six works over the past 10 years, including the ‘Guilt Trilogy’ consisting of ‘Replica,’ ‘Legal Dungeon,’ and ‘The Wake.’ Notably, he expressed a desire to create “a world completely separate from oneself,” which piques the curiosity of users who enjoyed ‘미제사건을 끝내야 하니까.’

Today, SKOOTA conducted an interview with SOMI, an indie creator gaining attention not just in Korea but globally. We aim to vividly convey his experiences and thoughts about the production of this work and topics many users of his games are likely curious about.

SOMI(소미)

Debuted in game development with ‘RABBIT HOLE 3D’ in 2014

Notable works: Guilt Trilogy ‘Replica’ (2016) ‘Legal Dungeon’ (2019) ‘The Wake’ (2020)

Latest work: ‘미제사건은 끝내야 하니까’ (2024)

Awarded at Indie Stream Festival in 2016

Awarded ‘Best Story Game’ at Indie Arena Booth in 2020

Awarded A MAZE./Berlin 2024 Grand Prize

Awarded ‘Excellence in Game Design’ at BitSummit Drift

Awarded ‘Jury Prize’ and ‘Social Impact Award’ at BIC Fest 2024, and more,

numerous awards

Currently balancing a career in the legal field along with indie development activities.

SOMI, a 20-year legal professional and 10-year game developer: “Game development started with chance and curiosity.”

――We are joined by SOMI, a well-known indie game developer making headlines not only in Korea but also in Japan. Could you please introduce yourself briefly?

SOMI: I don’t think I fit the description of being famous at all. I am just SOMI, making indie games alone in Busan for about 10 years now. I released ‘RABBIT HOLE 3D’ in 2014 and have since released six works. My notable ones include the Guilt Trilogy consisting of ‘Replica’ (2016), ‘Legal Dungeon’ (2019), and ‘The Wake’ (2020). This January, I released my latest work titled ‘미제사건을 끝내야 하니까’ (2024) and have been actively promoting it.

――It is also known that you are not a full-time developer, but balance your main job with indie development. Having been creating games for 10 years, what creative activities did you pursue before entering game development?

SOMI: During my college years, I had a strong desire to become a novelist, so I wrote short stories and submitted them to literary contests, striving to get published. While my skills were lacking and I couldn’t debut properly, that was my experience. Before that, in high school, I had thoughts of wanting to become a cartoonist, so I spent a lot of time copying and drawing comics.

――Can you explain how you transitioned from wanting to be a novelist or cartoonist during your college years to game development now?

SOMI: I majored in law at university and still work in a law-related job. I’ve been in the workforce for nearly 20 years now, so I’ve become quite accustomed to the routine of office life. During this process, I felt the need for my own creative activities, which serve as an outlet for my thoughts and stress relief. So, I decided to teach myself programming. I created apps and released them in the app store, such as an app for tarot card readings and another that sends emails one year later.

――From your description, it feels like rather than being tied to one thing, you have tried various things from multiple perspectives. What made you settle into game development?

SOMI: As I learned programming and created apps, I started to think about what my next project would be. At that time, I encountered a very popular mobile game called ‘Super Hexagon’ (2012). I thought it was an extremely well-made indie game. At that time, I didn’t even know what indie games were, and I didn’t play games much either. After playing it, I thought, ‘I could make something better than this with just a little effort,’ which was a rather nonsensical idea. That was the seed of what became ‘RABBIT HOLE 3D.’

――It’s hard to imagine you creating a work in the same tone as 『RABBIT HOLE 3D』 (laughs).

SOMI: Even now, I have a strong desire to make a rhythm game. So whenever I’m asked what I want to do next, I often say that I want to create a proper rhythm game. I also really like chiptune, and it’s like a small goal of mine to create an amazing rhythm game that surpasses ‘Super Hexagon’ with chiptune.

――You mentioned you made apps, and I heard that one of them ranked third in the Korean app store. It seems like the motivation for app development was stronger, but what motivated you to shift to game development?

SOMI: It feels very coincidental. The reason I started making apps was also quite random. Though I wouldn’t get into specifics, it occurred to me while brainstorming what my next app should be that a game which seemed simple could generate a remarkable response. So, I thought, ‘Can I do that too?’ which drove my initial attempts. As I worked more on games, it took a lot of time to realize how challenging it is to create a game and that even games that seem trivial require extensive research and effort.

From form to message: “Don’t bring politics into games.”

――Speaking of ‘curiosity’, I want to ask you one thing. You mentioned you created your first game out of curiosity, but what curiosity drove you in creating your representative works, the ‘Guilt Trilogy’?

SOMI: After making ‘RABBIT HOLE 3D’, I created a 2D puzzle platformer called ‘RETSNOM’ (2015). Through creating 2D games, I gradually established a direction that incorporated narratives within pixel art. When I was making ‘Replica’ (2016), after launching ‘RETSNOM’, I had an image of a mobile phone screen made in pixel art from an internet search that stuck in my mind. I thought, ‘Is there a game that made the whole screen look like a mobile phone screen?’ At that time, there weren’t any. I thought it would be lovely to present the entire screen like a pixel art mobile phone screen. In short, ‘Replica’ was a game made from the form first, with the idea that we should replicate a mobile phone screen within the game.

*The first work of the Guilt Trilogy.

――It’s shocking to hear that ‘Replica,’ the starting point of the Guilt Trilogy, was a game made from form first. You mentioned that the story was entirely different from the current version; can you elaborate on that?

SOMI: Initially, I aimed to create a story based on the novel ‘The Talented Mr. Ripley’ (1955). The basic storyline involves Tom, who kills someone and lives out that person’s life. He approaches Dickie, the wealthy man’s son, kills him, and pretends to be Dickie. The narrative explored how Tom, right after killing Dickie, holds his phone and invents an alibi to convince Dickie’s friends that he is still alive. I developed this story, introduced it to friends, and went through playtesting. Then, in 2016, significant events happened regarding the impeachment of then-President Park Geun-hye and demonstrations related to it.

Additionally, there were various instances of media suppression and blacklisting, leading to an increasingly authoritarian atmosphere. Watching other citizens fight in the streets made me feel shameful for doing nothing. I wanted to do something, and that made me think it might be worthwhile to convey that story through this game, prompting a complete change in the narrative. This marked the start of ‘Replica’ and initiated the ‘Guilt Trilogy.’

――You mentioned 2016. I believe many in Japan remember the significant events that year. I understand that these events influenced your creations. However, dealing with social issues through a medium like a game was likely met with more resistance than it is now. How did you feel about that at the time?

SOMI: I think it was quite rare to tackle social issues through games back then. I had never seen a game dealing with political issues or social problems occurring within the country. There were parody games in my childhood where presidents battled each other, but afterward, I don’t recall any works that directly or aggressively addressed social concerns. The approach to treating games as an art medium was, I believe, lacking, which perhaps narrowed the genre of games considerably.

Moreover, focusing solely on the notion that ‘games must be fun’ or ‘games should provide enjoyment’ can often suppress various paths achievable through the unique characteristics of the medium. Recently, shifts in this perspective have occurred, as games have gained a certain foothold as an art genre; yet the prevailing belief that ‘games are supposed to be enjoyable’ persists. I think game preferences vary greatly, which further highlights the importance of recognizing diverse genres and layers of enjoyment. Some people find joy in simple games like ping pong, while others derive thrill from analyzing narrative structures and character relationships. Young creators now recognize the potential of their games reaching a wider audience.

――I believe your thoughts are spot on. This seems to support the emergence of diverse games, including indie games, in this era. In this dynamic context, do you still hear the sentiment ‘don’t bring politics into games’?

SOMI: Absolutely. There are reviews of ‘미제사건은 끝내야 하니까’ stating that ‘It’s a game made to push a political agenda.’ During the rise of various feminist issues in Korea, I had strongly articulated my stance against ideologies aimed at repressing feminism, making me a target of criticism among players. I received lots of hateful comments. Even now, there’s a dichotomy in the online forums regarding the game, with one side saying, ‘This is a game made by a feminist developer, so we should definitely avoid it,’ while another side believes, ‘This person has a proper perspective, so this game is safe to play.’ It seems that discussing personal opinions, views, ideologies, or philosophy within the game remains quite taboo.

――I found it impressive that you expressed gratitude for being labeled ‘the best feminist.’ (laughs)

SOMI: I try my best to live up to that claim. It’s a matter of continuous learning.

What SOMI chose to erase in games was none other than ‘oneself’: “I wanted to create a completely fictional world.”

――Returning to the main topic, regarding ‘미제사건은 끝내야 하니까’, you mentioned wanting to create a ‘game with a face,’ in contrast to the previously mentioned Guilt Trilogy. What does ‘game with a face’ mean?

SOMI: Until now, the Guilt Trilogy had no illustrations of characters at all. As players engaged with dialogues, they would infer things like, ‘This character must look somewhat like this,’ or ‘This is their likely age.’ However, coincidentally, during the release of ‘LEGAL DUNGEON’ (2019), the game was launched with a terrible Japanese translation. Despite that, the creators of ‘The Gnocia’ reached out to me. They were about to release their game but offered to completely fix my translation while creating illustrations for it. After the switch version with the illustrations released, the responses from players were significantly different. It was mainly a difference of one illustration. Although the translation issues were resolved even before the switch version, the illustrations helped demonstrate that players could feel the presence of the characters.

――I heard that ‘The Gnocia’ recently got an anime adaptation.

SOMI: Yes, they are really amazing creators.

――Can we expect to see your works adapted into anime someday?

SOMI: That would indeed be a beautiful thing. To see a work like ‘LEGAL DUNGEON’ become an anime or a movie would be an incredible honor.

――Earlier, you mentioned that ‘having illustrations can limit imagination.’ Were you previously negative about illustrations prior to ‘LEGAL DUNGEON’?

SOMI: No, I didn’t think they were bad. Even when I created ‘Replica’ and ‘Legal Dungeon,’ I believed in creating optimal images. For example…

Well, I thought ‘Replica’ was essentially a game that didn’t need characters. By emphasizing the abstraction of characters, I aimed to demonstrate that these situations could be faced by anyone. Alternatively, I tried to highlight the prisoner’s dilemma or maintain focus on the phone’s functionality. In ‘Legal Dungeon,’ the rank insignia replaced characters during conversations. The aim was to emphasize that these individuals were treated not as humans but merely as parts of a machine. Furthermore, until just before the ending, the protagonist’s gender is never revealed, lending a sense of ambiguity that allows players to experience an unrestricted imagination.

――I see. Through the illustrations from Kotori-san, you’ve come to view your works in a new light, and it prompted you to think differently about creating a game with faces in ‘미제사건은 끝내야 하니까.’

SOMI: There’s also a bit of greed involved. This time, I had a personal desire to see proper representations of these characters.

Quoted from the PS4 release trailer.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Up95daqmWL8

Also quoted from the PS4 release trailer.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Up95daqmWL8

――After creating characters without faces, you transitioned to making characters with faces in ‘미제사건.’ How did this mindset influence the actual production?

SOMI: Creating characters with faces had a peculiar impact on me, revealing things I recognized later post-production. Unlike the Guilt Trilogy, the plot of ‘미제사건’ was developed first. In the trilogy, I began with the form, later embedding a narrative to match the theme within that form. In contrast, for ‘미제사건,’ I initially established the entire story, subsequently contemplating how to best represent that narrative in form, leading me to naturally focus more on the characters as I crafted the story.

――You mentioned that, unlike your previous works, you began with the narrative; my question is, in a past interview, you mentioned that while the message in a game is crucial, it also must be beautiful and should be important in itself. Could you elaborate on this statement?

SOMI: I don’t claim to have a perfect philosophy regarding that. However, while working on the Guilt Trilogy, I often felt like I was continuously gnawing away at myself during the game creation process. The guilt I felt and the changes I wanted to see in this society drove my desire to use this medium as a way to convey the message that I wanted others to experience these feelings and face the situations in the same way. This aspect was most amplified when creating ‘The Wake’ towards the end of the trilogy.

It is essentially my story, which contains exclusively my experiences. While this can serve as a means for me to alleviate trauma or underlying stress, I also felt it dangerously turned the game into something overly dependent on the author. So, when considering my next game, I wanted to create a ‘complete work of fiction.’ This means that the characters within could have no relation to myself at all. The episodes and feelings that emerge in the game should feel distantly removed from my reality and social experiences. I aimed to create an unfamiliar space, ensuring that even if SOMI wasn’t present, the world would still exist as a complete entity. I had this abstract thought of wanting to create a perfect world and my intention was also to convey a theme of beauty in conjunction with that world. Thus, my approach to games and subject matter evolved as a reaction against the views I previously held about my own games. Instead of adhering to a premise that ‘games should be like this,’ I thought about creating something new this time based on previous experiences.

――You expressed a desire to create a world that can exist without yourself, which simultaneously portrays a ‘warm and humane world,’ and that seems both complex and bittersweet. The notion that everyone experiences warmth and emotion through such a world suggests profound implications, doesn’t it?

SOMI: There’s certainly a bittersweet aspect to it. (laughs)

――Did you foresee that a world devoid of yourself would receive such acclaim and empathy, or did you find the outcome surprising?

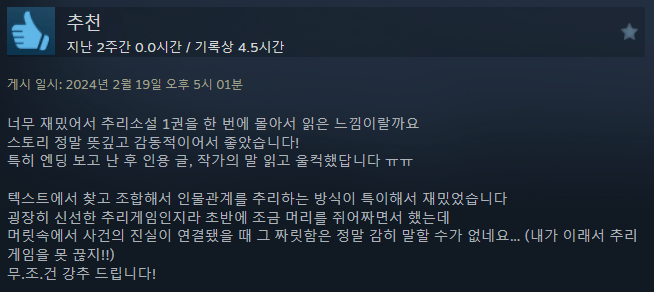

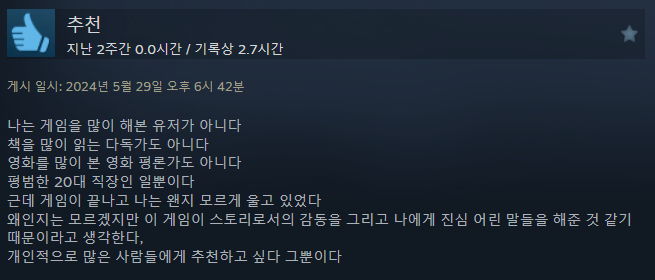

SOMI: I feel both ‘I expected it’ and ‘I did not expect it’ simultaneously. Before the release, my emotions were up and down. Some days I thought, ‘This is going to be a massive hit!’ Other days I thought, ‘Who would play such a boring game?’ While oscillating between these thoughts, my developer friends and publishers reacted negatively when I showed them the game initially. I then thought, ‘Ah, I guess I’ve made another self-satisfying game.’ However, later, when I sent it for localization, I asked the translators to play it first before starting the translation. Two days later, I received an email saying, ‘I cried a lot.’ At that time, there was no music yet. I was making the music while translating, and when I saw that email, it dawned on me: this was good! I felt a sense of reassurance, if that’s not too grand a statement, I felt saved.

――That’s a very impactful story. So you received that evaluation while in the process of localization. By the way, it seems that translation is a prominent topic in this interview; how did you proceed with the localization for ‘미제사건은 끝내야 하니까’?

SOMI: I had difficult experiences with translations gone wrong in the past. Until ‘Replica,’ I never imagined I could earn money through games, so the translations were terrible. After release, as it gained popularity, fans stepped up to help with translations one by one. For ‘Legal Dungeon,’ I decided to improve the translations and hired a domestic agency, but their English, Japanese, and Chinese translations were worse than machine translations, making it a disaster.

Ultimately, like I mentioned before, the translation for ‘Legal Dungeon’ underwent a fan-led process. From ‘The Wake,’ English translations became the baseline for other languages, so I sought out individuals who translated literary works abroad rather than looking for bilingual translators within the industry. However, many of those involved in the industry were quite busy and had no time for games. I reached out personally via email to those who had received awards for literary translations, and while many rejected due to it being games, through a persuasion process, I found the collaborator I’m currently working with. Thanks to them, the expressions in the English version of the game have been communicated effectively, and that continues for ‘미제사건’ as well.

――Are there specific points you are particularly mindful of in translation?

SOMI: It’s a trending expression nowadays, but how well can we convey poetic prose? That’s something I pay a lot of attention to during the translation process. Furthermore, translation and localization are quite different. Knowing how important localization is in Japan, I made efforts to ensure that the review process was thorough. In the case of ‘미제사건’, we went through this twice: first translating to Japanese, and then reviewing it again with someone knowledgeable not just about the translations but also about the nuances of the game and the Japanese sentiment. The content, atmosphere, and even the title can change in feeling based on word choice, including details like character dialogues or even the daughter’s name. For instance, we considered how to name the character Seika. What reading of the kanji will ensure the child isn’t teased at school? We continuously exchanged feedback on such matters.

Therefore, I prefer to work with translators who communicate frequently with questions. Each sentence has its nuances, and there’s a symbolic system within it. Some aspects can be verified from sources or other media, which makes communication crucial to produce a well-crafted text. I encourage translators to ask as many questions as possible.

(To be continued in the next part.)

![“We Must Resolve Unsolved Cases – Interview with Solo Developer SOMI [Part 1]”](https://skoota.jp/media/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/SOMI_サムネ(日本語)-300x169.png)

![[TGS2024] Did you know? You may have played it, but you might have completely missed out on “Korean” indie games.](https://skoota.jp/media/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/SKOOTA_TGSレポハナサムネ-300x169.png)